How do you raise thousands of wētāpunga in an efficient and sustainable way, that’s optimal for the species?

As invertebrate expert Ben Goodwin will tell you, good science means a succession of tweaks and revisions, before you arrive at the perfect conditions for life.

For someone so earnestly passionate about invertebrate conservation, it’s interesting to note that Ben’s first role at Auckland Zoo was caring for hooved species like giraffe and zebra, on what was then known as the ‘Pridelands’ team. Over the next few years, Ben honed his skills with a wide range of animals, including everything from reptiles, tarantulas, birds, and bats, to wallabies and kangaroos. This gave him a great foundation and sated his curiosity for diverse species.

Auckland Zoo’s stunning and expansive area for New Zealand species, Te Wao Nui, was completed in 2011, which brought with it an influx of taonga species to the Zoo. This increased focus on New Zealand’s flora and fauna also meant a greater emphasis on the conservation of these species, many of which are threatened or endangered – and was the catalyst for Ben to specialise in the care of reptiles, fish, amphibians and invertebrates.

One of the key projects the Zoo quickly established was the wētāpunga breed for release programme. Historically, the largest of New Zealand’s giant wētā were found from Auckland at its southern limit, to Paihia as its most northern limit, but due to habitat loss and introduced predators, had become restricted to just one island, Te Hauturu-o-Toi. The aim of this Department of Conservation (DOC) endorsed initiative was to restore the species to at least four additional islands, to mitigate its risk of extinction from a range of threats such as fire, extreme weather, disease, or predation – threats which are greatly exaggerated when a species is restricted to a single island.

Wētāpunga had been studied previously in the 1950s and 60s, yet this work had been primarily focused on their anatomy and biology - and invertebrate knowledge had evolved significantly since then. Butterfly Creek entomologist Paul Barrett had earlier been tasked with how to breed wētāpunga in a controlled environment, which involved creating a new husbandry protocol that factored in contemporary knowledge of insect care. This important foundational work led to an initial small group of wētāpunga being translocated to Tiritiri Matangi and Motuora Islands in 2010.

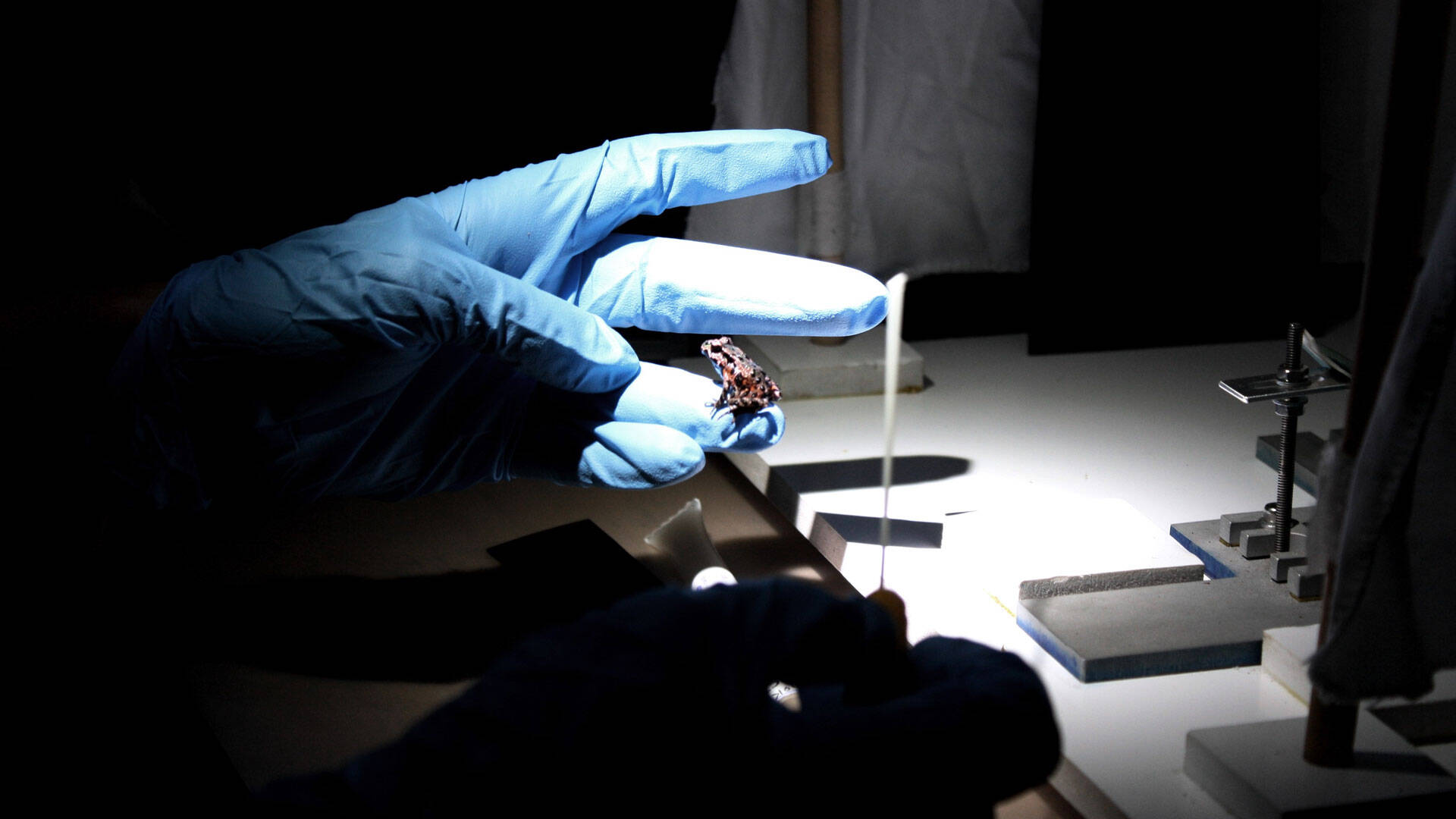

Auckland Zoo’s involvement began in 2012, which led to Ben and other members of the ectotherm team venturing to Te Hauturu-o-Toi for the first time to collect 12 ‘founder’ wētāpunga (animals that would go on to create the first Zoo-born generation) with the support of Ngati Manuhiri Settlement Trust and the Department of Conservation.

“Spending a lot of time exploring the island and being immersed within wētāpunga habitat was invaluable for the work we were doing, because the more experience you have with the species in the wild, the better understanding you have to bring back and inform their husbandry at the Zoo.

I’ve been to the island three times now, and each time has been better than the trip before. I feel like part of that is because my knowledge and appreciation for different aspects of New Zealand’s biology gets broader and broader. Going there was very important in my development as a conservationist,” explains Ben.

With the founder wētāpunga safely ensconced in a dedicated climate-controlled facility at the Zoo, our team started to explore breeding wētāpunga on a larger scale. The idea was to build on the existing husbandry protocols by testing a range of enclosure variations and group sizes – in the process learning more about how to rear the species and creating efficiencies in staff time and resources, whilst always ensuring optimal animal welfare.

“Most species of insect produce a lot of offspring and so it's really important to make the most of that – you don't want your rearing system to be what’s slowing you down. We wanted to make full use of the fecundity of each of those animals, so we decided to investigate communal rearing.”

The Zoo gained approval from DOC to hatch the first cohort of insects using the original methodology – with each wētāpunga in individual enclosures - and then for any subsequent offspring, to trial different types of communal rearing systems.

“We were hoping that we would get a few more hatchlings to trial these new methods. What actually happened was that we got hundreds more! We produced so many animals in that first year, and they just kept hatching and hatching and hatching.”

Some of the key conditions that Ben and the team were examining were – how does the density of animals in each enclosure affect their survival rate? And what is the factor that influences that – is it the amount of hiding places, is it competition for food?

“That sounds easy when you say it like that - but this involved a lot of careful enclosure design and constant data collection. Our wētāpunga breeding room contained floor-to-ceiling shelves loaded with enclosures of different shapes and sizes, with different densities of animals – and handwritten notes everywhere – it was chaotic but a great exercise. At the end of it, what we achieved was hundreds of animals for translocations and a good idea of the right density, the right enclosure size, the right availability of hiding places and knowledge of how to distribute food within those enclosures.”

The majority of the animals bred in that first season were translocated to Tiritiri Matangi and Motuora islands with 10 pairs of wētāpunga kept back at the Zoo to breed the next generation. The team were able to successfully repeat their success with this second generation which created a very streamlined way of rearing with predictable outcomes.

Feeling confident in their approach and successes, the team began looking for additional islands that would be suitable for translocation. In 2014, Ben travelled with colleagues to Motohoropapa and Otata islands to assess their suitability for these giant wētā. They were joined by owner Rod Neureuter and a few ex-members of the wildlife service who used to periodically live out on Motuhoropapa in the 1970s, experimenting with rat eradication techniques.

There are several key criteria of suitable wētāpunga habitat which require assessment; the abundance of hiding places, the availability and distribution of favoured food species such as mahoe, Coprosma, titoki and kawakawa, the assemblage of native and non-native predators present, and the history of the islands – for example, how susceptible are they to rat invasions, as well as climate and exposure to the elements. It was clear that these islands provided an exceptional habitat for this precious species, and the Zoo submitted a translocation proposal which was quickly approved by DOC.

“The wētāpunga project was a good demonstration to me personally that contemporary zoos should be putting more of their conservation resources into invertebrate conservation. You get so much bang for your buck and they’re so well suited to these kinds of programmes. Insect biology is such that they can produce a significant amount of offspring – often in their thousands – and they take up a small physical and financial footprint when compared to larger species. I was keen to show other people the value of this work – which led to doing public and community talks.”

Awareness of the Zoo’s mahi on this project had spread, which lead to our being approached by community groups Motuihe Island Trust and then Project Island Song to translocate wētāpunga to Motuihe Island and the Bay of Islands, respectively. Ben and the Zoo’s ectotherm team leader spent a week assessing seven of the islands within the inner Iripipi / Bay of Islands group, which led to three being identified as providing suitable habitat for wētāpunga - Urupukapuka, Moturua and Motuarohia. Following two more years of breeding and rearing, wētāpunga, were transferred to Bay of Islands, effectively restoring them to this region for the first time in 180 years.

“We have collectively achieved more than the recovery programme set out to do, which was to establish wētāpunga on four more offshore islands. Through ongoing surveys and monitoring by the Zoo and DOC, we know the species is established and persisting on Tiritiri Matangi, Motuora, Motohoropapa and Otata islands. Moving forward, it will be great to demonstrate what these populations are doing over time in four radically different habitats. In a couple of years, we’ll be able to tell if the species is still persisting on the additional four islands where the species was released.”

Video

Keeper Chat

Ben tells us more about the Zoo's breed for release programme for wētāpunga.

In Ben’s 14-year conservation-focused career at Auckland Zoo, he was lucky enough to travel to some intrepid destinations and every trip increased his appreciation for endemic species.

“I’ve been able to travel to some pretty amazing places. I've visited many of New Zealand’s offshore islands for fieldwork, and each one is that little bit different. It's so appealing to me because I have this really broad interest in natural history and being immersed in that environment teaches you so much; there are lots of cool plants and animals to discover and interesting things happening ecologically. It's been an incredible opportunity to be able to do that.”

One island that Ben travelled to multiple times as part of the Zoo’s conservation fieldwork programme was Rangitoto.

Zoo staff visit the island quarterly to survey and collect data on how the distribution of several reptile species is changing over time since the eradication of mammal predators. This includes species such as the moko skink (Oligosoma moco), copper skink (Oligosoma aeneum), raukawa gecko (Woodworthia maculata) and New Zealand’s only egg-laying skink, Suter's skink (Oligosoma suteri). “To be welcomed and have the opportunity to stay on Rangitoto Island for five days at a time, and be fully immersed in that environment every day is amazing,” explains Ben.

Further afield from the Zoo, Ben spent time searching for the Mahoenui giant wētā in the King Country. The farmland where this wētā was discovered was purchased by DOC and turned into the Mahoenui Giant Wētā Scientific Reserve, with their population and threats monitored annually.

“It’s a pretty famous area in terms of its ecological bizarreness. This is a highly threatened species that continues to survive when all of its close relatives, as well as native species that have occupied similar niches, have gone extinct on the mainland and are now restricted to offshore islands. Yet, it survives in a patch of gorse! This was a species I read about when I was just starting out in conservation, and to actually see it for myself was pretty wild.”

The predominant theory is that the incredibly high abundance of goats in the area browse the gorse back so it’s dense and thick. This makes it so impenetrable that introduced predators, especially rats, aren’t able to get through to the wētā to eat them. Remarkably, this makes it the only reserve in New Zealand where gorse and goats are protected!

Wētāpunga are a real flagship species for the kind of work that Ben sees as being so important - and a testament of what can be achieved in zoos. Yet, there are many smaller and less charismatic species that often fall under the radar of public awareness.

“I’m really proud of working on this project, with our wider team. The conservation of insects and other less charismatic species can be overshadowed by bird conservation. But every species is unique in its own right, and is part of an intricate web of biodiversity. I’m hoping this project has paved the way for others to be inspired by what can be achieved for a myriad of other species that are also at risk of extinction.”

If you want to learn more about some of these endemic treasures, check out previous blogs Ben has written or co-written on the Pollen Island moth (Bactra ‘Pollen island’), kahukura (Vanessa gonerilla), the New Zealand bat-fly (Mystacinobia zelandica), Taumaka leech (Hirudobdella antipodium) and New Zealand’s endemic mosquitos.

Video

Establishing Wētāpunga on Motuihe Island

Follow Auckland Zoo's ectotherm keepers as they set out to release zoo-bred wētāpunga on Motuihe Island