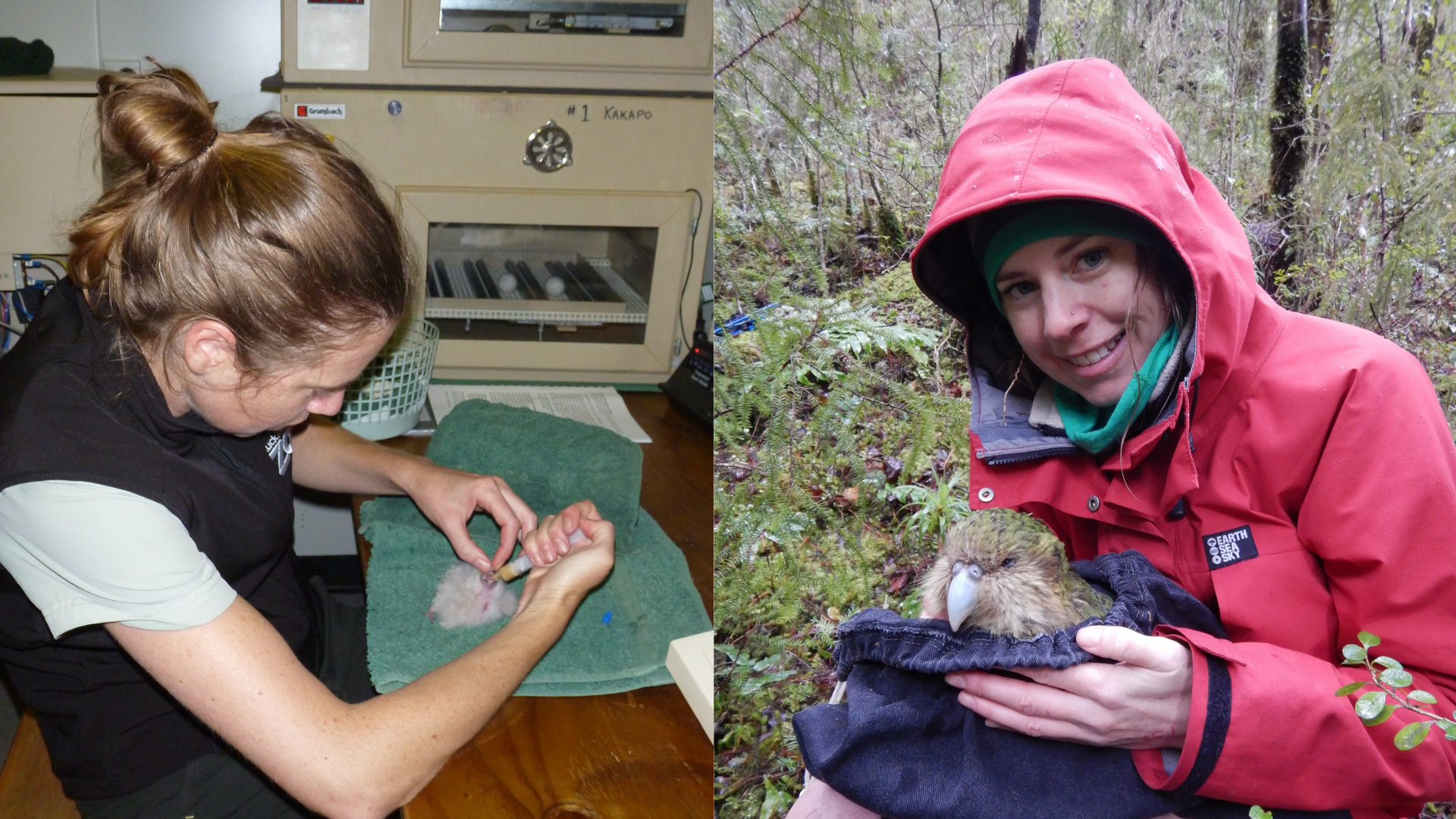

Working with animals, in a world-leading zoo, as a veterinary nurse, sounds like a dream job to animal enthusiasts far and wide. After sitting down with Auckland Zoo Clinical Coordinator, Mikaylie Wilson, I seriously doubt many could actually fathom what zoo veterinary nursing may entail, as she tells me about the time she spent a month bathing from billabongs, with wild guests of the crocodilian and dingo kind – all in the name of conservation. Exuding confidence and competence, you just get the feeling that this woman is tough, she’s seen it all and done it all, and for New Zealand Veterinary Nurse Awareness Week, she absolutely deserves a celebration of her career.

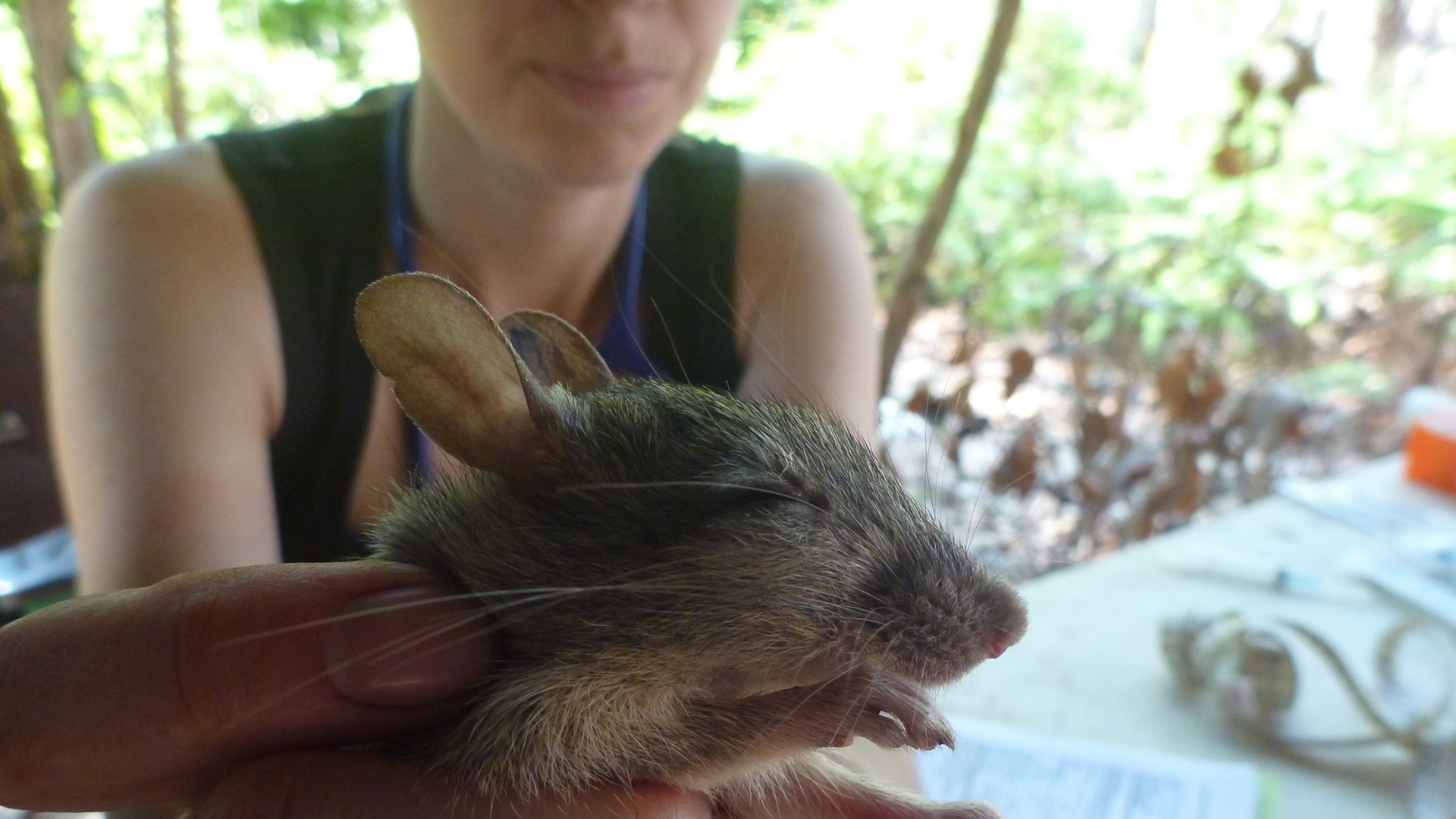

Arnhem Land, in Australia’s Northern Territory, is a rugged wilderness characterised by rocky cliffs and ridges, gorges, rivers and waterfalls. Most notably it’s home to Aboriginal landowners, and has been for tens of thousands of years, with permits required to enter. Sent in with a month’s worth of supplies, and dealing with zero basic amenities, extreme heat, and some tough yakka ahead, you wouldn’t be far off the mark to imagine a ‘Man vs Wild’ situation. Yet when asked about a defining conservation project in her career, Mikaylie speaks fondly of her time in Arnhem Land, where she was sent in by the Northern Territory State Government to research the effects of bush fires and controlled burn offs on local wildlife, and got to experience this magnificent landscape in a vet nurse capacity.